At the beginning of 2019, we asked authors to submit answers to a few questions in the hopes of giving our readers some insight into the various methods writers use to produce their mystery fiction. We got lots of terrific answers, as varied as their writing. Here are the replies of four of the responders.

Let’s first welcome JODI RATH this month as she explains her process to us.

BIO: Moving into her second decade working in education, Jodi Rath has decided to begin a life of crime in her The Cast Iron Skillet Mystery Series. Her passion for both mysteries and education led her to combine the two to create her business MYS ED, where she splits her time between working as an adjunct for Ohio teachers and creating mischief in her fictional writing. She currently resides in a small, cozy village in Ohio with her husband and her eight cats.

You have a new idea for a mystery that you want to develop into a book or short story.

What are your first steps in developing the idea to transform it into a novel-length piece? What’s the first thing you do after jotting down the initial idea?

For book one—it started about seven years ago with an idea of two best friends trying to solve a murder. At the time, I knew I wanted to write a mystery. I wasn’t stopping to think about different subgenres within mysteries. The book began in early stages is a “traditional” mystery in that murder happened on the page; there was violence; there was language. I really did not know what I was doing. I was working a full-time job teaching and trying to write. There was no real plan, and the draft was a mess and only one-quarter of the way done. It hit a drawer and I walked away for many years.

February 2018, I came back to it with a sense of understanding subgenres in mystery. I knew I wanted to write a cozy mystery—so there was a lot of work to be done on the little I had written at that point. I kept the main characters, Jolie and Ava, from what was called Strange Blue and switched the book to a cozy series called The Cast Iron Skillet Mystery Series and book one was Pineapple Upside Down Murder.

How it went from traditional and the difference in stand-alone to series and title is as follows: I live in a small village. I grew up in the inner city. I read all types of genres. I connect most with cozies. So, I decided on cozy as the genre. Next, I knew it would be a series, so I needed the theme of the series. On December of 2017, my grandma gave me her 70-year-old cast iron skillet and told me she had only ever made pineapple upside-down cake in it. This is where I got the series title and title for book one. I have eight cats and know many people love animals so all of my cats will be on a cover at some point and often mentioned in the books.

Once I knew the series and title and had the idea—I began plotting. Who is the victim? Who is the killer? Who are the suspects? What is the motivation for the killer and the suspects? What clues need to be planted?

What additional things do you do to shape that idea so it becomes the mystery you thought it could be?

I take a lot of dynamics of the people I know, my family, and myself and insert it into the story. So, to date, I have not felt that I’ve ever experienced writer’s block once I started the series. I did experience it when I was writing the original manuscript. Once I got the idea for the series and book one, this is the point where I began to add aspects of all of my friends into Ava—Jolie’s best friend—those characteristics of my friends show up in other characters too. Jolie is a lot like me, but she is very different in many ways too. Grandma Opal comes from my Grandma Walton. If I ever hit a difficult area within the story or while plotting it out, then I just pivot and think momentarily about different things I’ve witnessed my friends or family going through or my previous students, etc.

Do you use Character Charts, plot outlines, pictures, notebooks, bulletin boards, etc.?

Yes, I use character charts, plot charts, pictures, notebooks, and bulletin boards.

Which methods have you tried and which have worked best for you?

Once I answered all those questions and knew I will use information from people I know, then I had to create a chart to keep all my characters straight and all the descriptions and their personalities and things in order as I continued to write the book and the rest of the series.

For example, after book one came out November of 2018, I joined in a Valentine’s Day anthology with eight other authors. I did not have time to write a full novel based on my deadline for book two, Jalapeño Cheddar Cornbread Murder, so I chose to write a 9,000-word short story called “Sweet Retreat,” which picks up a few months after book one left off and will lead into book two. The anthology is called Cozies with Heart. The chart that I created with characters helped me write the short story, and it was a quick reference to look back to in helping to remind me about characteristics, pets, names of pets, occupations, family dynamic, etc.

Before writing book one, I had to create a map and come up with the name of the village and all the places in the village and set the map up to help me write about location, etc.

Next, I added to my chart document a second chart with plot lines. I chart and track plot lines of each book, flash fiction piece, short story to avoid repeats and to help remind me of who have been suspects before.

I have a whiteboard that I call my murder board where I keep visuals as well as plotting ideas. The one thing I always keep on this board on the left-hand side is a reminder to write to the blurb I created for the written piece (I write this before writing the book) and the cover. Also, I keep a triangle that shows me the elements of story writing as a reminder, and I keep the letters “G,” “M,” “C,” which stands for ‘Goals,’ ‘Motivation,’ and ‘Conflict.” The entire book and the entire series revolve around GMC.

Lastly, I keep notebooks of different projects I work on, and I journal to self-reflect on each project at different stages. There are times when I will pivot a bit based on self-reflection, but I tend to frontload in research of the process to figure out what works best for my personality and my organizational tendencies. I remember wanting people to tell me their process so I could do THAT . . . Well, THAT didn’t always work for me—maybe parts would. I had to work through figuring out the process that works for me to create what I create.

All of these things help me to shape the book before I even started to write it out.

Depending on the method you use, how successful has it been in fleshing out the idea? Or, do you begin with one method and find yourself gravitating to another?

So far everything I do works well for me. I own a business that has two sides to it. One side is educational writing on deadlines and teaching online courses at the graduate level from home. The other side is writing mysteries. For me to keep up with the deadlines and the five courses I teach online while being on a deadline for mysteries, I must have a process that is organized and keeps me moving forward on all fronts. I have a method and stick to it because it is working for me. If and when it stops working, then I will gravitate toward another method.

Do you find that the original idea changes as you work with it?

Yes, for book one I had one killer in mind. Then, I really grew to love her and that she had a lot of sass. I liked that she and my protagonist were friends with issues. I wanted that to continue. So, I ended up changing the killer to keep this character throughout the series.

Does the idea ever become something entirely different than when you started?

Yes, see above.

Does the method you use allow flexibility in development? How?

It’s difficult for me to wrap my mind around writing without flexibility. If there are writers who do that, then I’d love to read about that. Writing is fluid. Yes, I can have a process and be extremely organized in that process, but as I commented on earlier—there are SO many variables when you get into writing the story. Just like my example of loving the killer in book one, that changed the entire book and will affect the entire series as well. How can that not happen?

Choose a novel of yours and walk us through its development from idea to finished work. Please tell us about the methods used and how the idea changed, if it did.

Answering the above questions explained the development of the idea. Also, I discussed creating a map, charts, murder board, visuals, notebooks, and self-reflection as part of the process in planning before, during, and after the writing. What I didn’t answer is the blood, sweat, and tears of writing—at least for me. Coming up with the idea, organizing it all, and tracking it all was easy for me. Writing the first draft of the story was fun. Once all of that is finished, this is when I have to get into what I consider to be the meat of the project. To get to the finished project, I have to revise then and edit. I must realize where I fall short—look at structure—look at the parts and whole. This is difficult, to say the least. It’s like putting a puzzle together, which is ironic because one would think the puzzle would be the mystery. I say, NO! I know who the killer is and the suspects and the why and how. What I don’t know is where to add some of the clues. How do I make subtle hints without giving away the killer to the reader? How do I get the reader to pivot and really hone in on a red-herring?

OH, and subplots! Oh boy, and the twists! OY, and the perfectionism! Let’s start from the last exclamation and work back. I am a perfectionist. One of the only things I hate about the process of writing is that book one will always be my worst book. I’m not saying it’s a bad book, but it was the book where I learned a lot about what to do and not to do. I will get better with each book, and I will hit a groove hopefully sooner than later. That sucks for me!

Next, once the book is written, then I must look at the pace as one of the many things to look at. Pace is determined by how many twists occur in the plot. I find it difficult to go back to a finished product and see places where the pace dips for too long and then add a twist without rewriting the entire book, but I learned how to do it—kind of.

Subplots . . . My nemesis for book one. I like book one. I like the characters, the village, the story, and the mystery behind it. It is a bit linear in plot, and I learned from book one that concerning structure—I needed to research and read some craft books on subplots. So, I did. I learned. Now I’m close to being finished with book two that comes out June 21, 2019, and there are subplots—YAY!

Getting to the finished product is the goal of every writer. The stamp of PUBLISHED whether self-publishing, hybrid, or traditional—in that we are all the same. Writing is, in my mind, exactly like life—it’s survival, and it’s a journey . . . And I LOVE every minute of it!

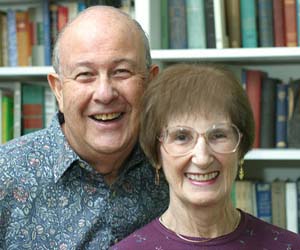

Next up is the writing team of ROSEMARY & LARRY MILD.

BIO: Rosemary and Larry Mild, cheerful partners in crime, announce their new thriller Honolulu Heat, Between the Mountains and the Great Sea—the sequel to Cry Ohana, bringing back the same Hawaii families that readers so warmly embraced. Coming in 2019: Copper & Goldie, 12 Tails of Suspense, featuring a disabled Hawaiian private investigator and his golden retriever partner. The individual stories have been entertaining Mysterical-E readers for several years. In addition to their recent sci-fi novella Unto the Third Generation, the Milds coauthored two cozy (traditional) series: the Paco & Molly Mysteries and the Dan & Rivka Sherman Mysteries. Death Goes Postal is now also a talking book on Amazon’s Audible. Visit the Milds at www.magicile.com.

You have a new idea for a mystery that you want to develop into a book or short story.

What are your first steps in developing the idea to transform it into a novel-length piece? What’s the first thing you do after jotting down the initial idea?

As coauthors, we identify five steps. One: Does the idea offer a valid motive for committing a crime? Two: Does the idea feature characters who are unique, shrewd, quirky—worthy of either solving or committing a crime? Three: Is the crime itself clever and fascinating enough to sustain a full-length mystery novel? Four: Do we have enough personal knowledge or research available to support such an idea? Five, is there a likely readership for such an idea?

What additional things do you do to shape that idea so it becomes the mystery you thought it could be?

We play the “What if?” game to explore how the basic idea might be executed (pun intended). We define plotting goals and the possible paths to achieving them. We then determine our initial research needs and our individual assignments to begin the story.

Do you use Character Charts, plot outlines, pictures, notebooks, bulletin boards, etc.? 3a. Which methods have you tried and which have worked best for you?

Larry: I‘m more devious than Rosemary, so I take primary responsibility for the plot. I write a ten- to fifteen-page statement of work to convince us both that we have a viable plan. The above aids are far too confining for me. As the characters bloom and the plot flashes create twists and turns, they reshape many of my original concepts. They might even take the story right out of my hands. I write the first skeletal draft. It’s that first draft that I enjoy writing the most.

Rosemary: When Larry turns the manuscript over to me, I’m responsible for breathing life into the characters. I create small bios for them, often using magazine pictures of people to make them more real. I also enhance scenes. Larry might have a great nugget told second-hand; I turn it into real-time for more drama and conflict. Larry does excellent historical research. I keep newspaper clips and do Google searches to get details right—like, I discovered I shouldn’t have given a revolver a safety. After completing my draft, we negotiate! (I’ve gotten more diplomatic over the years. No more tantrums.) Then we attack a third draft, attending to character development and scene dressing. As the chapters appear, Larry writes ten- or twelve-sentence chapter summaries to keep track of where we’ve been. Thank heaven for them!

Depending on the method you use, how successful has it been in fleshing out the idea? Or, do you begin with one method and find yourself gravitating to another?

Our method has been relatively successful in all of our nine published novels (and two volumes of short stories). Nice reviews support that success. After much experimenting during the writing of our first mystery, we’ve become quite compatible in our process.

Do you find that the original idea changes as you work with it? Does the idea ever become something entirely different than when you started?

Writing a book is a dynamic enterprise, and an author should never shut his or her eyes to worthy change. We have even swapped murderers when the original one seemed too predictable.

Does the method you use allow flexibility in development? How?

Of course! We chose it for its flexibility. It allows the actual character and plot history to dictate where and how each element is going to develop further. We’re gotten pretty receptive to each other’s ideas if a plot needs adjusting. Besides, we’re always learning: writing classes, writers’ conferences, workshops, and listening to other writers in our monthly meetings of Sisters in Crime/Hawaii and Hawaii Fiction Writers.

Choose a novel of yours and walk us through its development from idea to finished work. Please tell us about the methods used and how the idea changed, if it did.

We needed a fresh idea for our third Dan and Rivka Sherman Mystery. The first in the series, Death Goes Postal, featured printing relics from Gutenburg’s time. In Death Takes A Mistress, the driving force was a young woman’s quest to avenge the murder of her mother. For our third one, we found a worthy subject in our own guest room closet! Death Steals A Holy Book is based on a rare volume that Larry inherited: the Menorat ha-maor (“Candlestick of Light”), written in Yiddish and published in 1789. The original book was written in Hebrew in the fourteenth century—a guide to righteous living for Jews in the Middle Ages. Our copy was in critical condition, and we were in no position to restore it, so it now rests in the Klau Library Rare Books Collection of the Hebrew Union College, Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati.

In Death Steals A Holy Book, Dan and Rivka Sherman discover this same translation of the Menorat ha-maor in a hidden cache in their Olde Victorian Bookstore and take it to Israel Finestein, professional book restorer. But Izzy is murdered in his Baltimore shop, and the precious book is stolen. The location, size, smell, and layout of the shop prove important to both witnesses and suspects, so we established characters who either wanted Izzy dead or just wanted the manuscript and Izzy happened to be in the way. Peggy, Izzy’s fiancé, is the prime suspect because she’s found in the shop. Other suspects include a rival book restorer; a book broker strapped for cash; Izzy’s misguided cousins; and the wayward lad who thinks a gun is the way to big bucks. An intriguing motive was created for each suspect.

We also installed a few entertaining characters who simply move the story along. Ivy, the bookstore clerk, stars in a subplot to create suspense by taking the reader away from the main story just when the next clue is about to be revealed. She’s pitted against Mae, a disgruntled gold-digger. Conflict, suspense, humor, or misdirection is injected into almost every page. Balance is struck between dialogue and narration. A crucial character is Lord Byron, the Shermans’ cat who sleeps in the Poetry stacks and unconsciously exposes a suspect. The climax occurs during Peggy’s two-chapter courtroom trial, when an accidental event reveals the actual killer/thief. Leon, the dynamic lawyer, leads the courtroom drama.

Next we did critical read-throughs: for plot viability and the solution; and for continuity and writing quality. After Larry formatted it in Adobe’s InDesign program, Rosemary copy-edited it for spelling, punctuation, grammar, and consistency of style. Then, each at our own computers, we took turns, a page at a time, to read aloud to each other. Once satisfied, the book went to the printer. When we received the paperback proof copy a week or so later (as well as an e-proof), we repeated the read-aloud process and then approved it for printing—unless some wayward errors were found, and that meant redoing some part of the cycle.

The third featured author is Madeline McEwen, with an artistic approach.

BIO: Madeline McEwen is an ex-pat from the UK, bi-focaled and technically challenged. She and her Significant Other manage their four offspring, one major and three minors, two autistic, two neurotypical, plus a time-share with Alzheimer’s. In her free time, she walks the canines and chases the felines with her nose in a book and her fingers on a keyboard.

You have a new idea for a mystery that you want to develop into a book.

What are your first steps in developing the idea to transform it into a novel-length piece? What’s the first thing you do after jotting down the initial idea?

First up, I have a confession–I am a panster, not a plotter. For me, this means I have to get the idea or clue or particular line down on paper. It doesn’t matter if it is the beginning, the middle, the end or anywhere in between. Because my lifestyle is more complicated than some other writers, this generally means I have to keep it in my head for an indefinite period of time until I can reach a pen and post-it note or make voice memo on my phone.

What additional things do you do to shape that idea so it becomes the mystery you thought it could be?

Generally, I sketch, paint and doodle images that tap into the mood of the story. Since I err on the side of cozy mysteries, cartoons sketches keep in in the correct frame of reference.

Do you use Character Charts, plot outlines, pictures, notebooks, bulletin boards, etc.?

Which methods have you tried and which have worked best for you?

Definitely pictures [see above] but I also troll the internet hunting down images of my villains and my full cast of tertiary characters.

Depending on the method you use, how successful has it been in fleshing out the idea? Or, do you begin with one method and find yourself gravitating to another?

I place the character’s image on an A4 sheet and type out all their characteristics, quirks, and habits for easy reference. My room should resemble the National Portrait Gallery, but it’s more of a scruffy Scout hut.

Do you find that the original idea changes as you work with it?

Does the idea ever become something entirely different than when you started?

Yes. Always, and therein lies more than half the fun. I am a radio [and podcast] fan and often listen to authors talking about how their characters forced them to write in a particular manner. I considered this viewpoint half-baked, unlikely, or at worst, a big fat fib. Turns out, they told the truth.

Does the method you use allow flexibility in development? How?

Yes. Unlike authors of old forced to use a quill and a pot of ink, today many of us enjoy the freedom of a computer. Cut and Paste was invented with us in mind.

Choose a novel of yours and walk us through its development from idea to finished work. Please tell us about the methods used and how the idea changed, if it did.

My novelette, Tied Up With Strings, started with the premise that some autistic people, such as my two sons in particular, always tell the unvarnished truth and rarely approach strangers unless they have an important mission, usually greater than themselves.

One of my characters, Peter, adores all animals, especially cats. Peter tolerates man’s inhumanity to man, but cannot abide cruelty to animals. An incident motivates Peter to step out of his comfort zone. However, his actions are non-conformist, and not the choice of the average person. The whole story is hinged on this principle.

From experience, I could have chosen any number of seemingly bizarre actions, but instead picked something that most readers can appreciate—the desire to do good. From there, I took my erstwhile amateur sleuth and moved her from San Jose, and threw her into the UK at Christmas time for more comedic opportunities. A sense of humor is essential for survival in both real life and in fiction.

We hear from P.A. De Voe last, who takes us to far-flung shores with her fiction.

BIO: P.A. De Voe is an anthropologist with a PhD in Asian studies and a specialty in China. She has authored several stories featuring the early Ming Dynasty: The Mei-hua Trilogy: Hidden, Warned, and Trapped; A Ming Dynasty Mystery series with Deadly Relations and the forthcoming No Way To Die; Lotus Shoes, a Mei-hua short story; and a collection of Judge Lu short stories. Warned won a Silver Falchion Award for Best International Mystery; Trapped was nominated for an Agatha Award and was a finalist for a Silver Falchion. Her short story, The Immortality Mushroom, (a Judge Lu story) was in the Anthony Award winning anthology Murder Under the Oaks edited by Art Taylor. For more information on P.A. De Voe and her writings go to www.padevoe.com.

You have a new idea for a mystery that you want to develop into a book.

What are your first steps in developing the idea to transform it into a novel-length piece? What’s the first thing you do after jotting down the initial idea?

I write Chinese historical mysteries set in the early Ming Dynasty (late 1300s and early 1400s), so the first thing I do is read through various Imperial China legal cases to get an idea of what was going on and how the court dealt with the problem. I am usually looking for a case that would highlight a particularly interesting cultural/legal element. For example, how a crime was considered the responsibility of not only the actual criminal but also of his father. Collective responsibility was an essential concept behind early Chinese law and creates interesting dilemmas in developing a story. Deadly Relations, the first book in my new A Ming Dynasty Mystery series, came from this perspective.

The next thing I do is decide who the criminal is (by such things as gender, position in his/her family, and social class), why they broke the law, and who else would be held responsible for that person’s crime.

What additional things do you do to shape that idea so it becomes the mystery you thought it could be?

Next, I think about the surrounding characters who add dimension and texture to the story. In No Way to Die, the second book in A Ming Dynasty Mystery series, which will be launched in a few weeks, I again have two protagonists, a male itinerant scholar and a female women’s doctor. He can move easily through wine houses and public spaces, so I look for characters that he would run into. The women’s doctor has access to the world of women which would be closed to the scholar. I try to populate their world with characters that have interesting personalities and dilemmas.

Do you use Character Charts, plot outlines, pictures, notebooks, bulletin boards, etc.?

Which methods have you tried and which have worked best for you?

I make a detailed outline of my stories before I begin to write. I am definitely a structured person. However, I consider my outline to be a roadmap not a concrete structure my story is trapped inside. That is, I know where I’m going and also have the freedom to add a secondary road if I need to in order to develop a subtheme or accent a particular clue or red herring.

I write the first draft in Scribner; therefore, I do add pictures, brief character descriptions, and notes, including research links—all of which are easily accessible to me as I write.

Depending on the method you use, how successful has it been in fleshing out the idea? Or, do you begin with one method and find yourself gravitating to another?

My method works for me. Even if I have to stop writing for a few days or weeks, I always know exactly where I’m going when I get back to my work. This is especially helpful to me because otherwise I might forget what I was doing and would have to essentially rebuild my story. At the same time, if a new idea developed during the break period, I can easily slip it into the ongoing manuscript.

Do you find that the original idea changes as you work with it?

Does the idea ever become something entirely different than when you started?

So far this has never happened. If I were a pantser or organic writer, it might. With the way I work right now, if an idea was going to radically change, it would happen while I was still in the mulling over stage not the writing stage.

Does the method you use allow flexibility in development? How?

I think so. As new ideas or interests developed while writing a couple of my novels, I added chapters and scenes that weren’t part of the original outline. It was easy to tie them into the on-going work.

Choose a novel of yours and walk us through its development from idea to finished work. Please tell us about the methods used and how the idea changed, if it did.

Let me tell you about how I managed to write No Way to Die. This should show how flexible and useful an outline can be.

When I started the new series A Ming Dynasty Mystery, I wanted to use two protagonists because of the divided worlds of males and females in Imperial China. Normally, I wrote from a single POV, so this was new ground for me. When I wrote the first book in A Ming Dynasty Mystery series, Deadly Relations, my task was easy. Unfortunately, when I embarked on the second novel, No Way to Die, I immediately ran into problems developing the female side of the story. I went through the process described above for the overall project. I decided on karma and people’s reaction to the pervasive belief as an underlying theme. Developing the male side went quickly.

For the female side, the doctor Xiang-hua was modeled on a real women’s doctor who lived during the Ming Dynasty, so I was comfortable with the idea that she was historically possible. But, what about the other women I needed to populate my story? What would they be like and still be as historically appropriate as possible? I was stuck. As many historical authors know, women are typically left out of historical records unless they are empresses, queens or such. I decided to simply write up Shu-chang’s side (my scholar) of the story, hoping that a hidden pantser in me would produce a possible—and historically reasonable—female side. No such luck.

Finally, at one point I accompanied my husband on a trip to another state. I took a few books along and spent a long day in a local library going through the lives of women living in Imperial China. Most of them were written about as ideal stereotypes of womanhood. Three women, however, stood out. For one thing, the records (written by men in their lives) showed their specific religious beliefs and experiences, their behaviors, and even their family situations–which were not necessarily flattering to the husbands. Eureka! I had a new set of characters with examples of actual beliefs and behaviors. The records even brought together my interest in the nexus between religion and science/medicine. By the end of the day, I had written up a possible story-line for Xiang-hua’s side of the novel, interweaving the female piece with the male piece of the mystery.

For me, this worked. Through my original outline, and the flexibility Scribner software gave me in plugging in new chapters and scenes, I was able to bring Shu-chang and Xiang-hua’s stories together into one reasonable mystery. No Way to Die came out mid-March, so you can judge for yourself whether I succeeded in using a two-person POV with a cast of interesting and historically appropriate characters.

Thanks so much for having me here. I enjoyed thinking through how I write! Also, I LOVED reading what the other authors do for their processes too! Kaye George, you are the BEST!

It was a pleasure to be in this blog post and to read how differently we all write. It just goes to show that we each have to find our own way. Thanks for putting this together.

Thanks for all 4 of the contributors to this issue. I loved learning about all your processes and hope the readers did too!