MURDER UNDER WAY by Charles Schaeffer

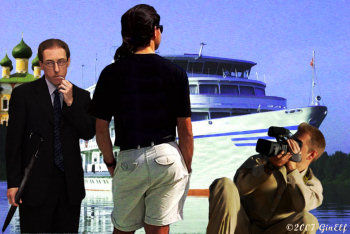

Tony Saunders eyed the traffic-clogged main street. Hardly Broadway and 42nd, even after Giuliana cleaned it up. Tony had argued for Bermuda , Spain , even Bosnia – anywhere but a Russian boat trip on the Volga . Janice, though, stood firm through all his bluster. An uplifting experience was the best medicine for Tony Saunders, overaged playboy. Ahead of them stretched Moscow 's main street, St. Petersburg Highway , but oddly still clinging to the alternative, Leningrad Avenue . A gray city of ten million, its dwellers pack cars, trucks and assorted conveyances into every inch of space. Even open spots on the sidewalk filled up, fair game to the first-come-first served commuters, heedless of tickets they wouldn't pay anyway. At the red wall surrounding the gold domed Kremlin, the tour bus dropped off Tony, Janice and forty fellow tour members, mostly wide-eyed Americans. Like a Bengal Lancer, tour guide, Helmut Freed, charged ahead, holding aloft the company's green and yellow identifying flag. “Kremlin means simply ‘fortress',” he called in perfect Oxfordian English over his shoulder. “Kremlins, or fortresses, exist in every sizable Russian town.” Born in Holland now living in Russia , Helmut was full of such trivia, as well as other things. The Kremlin gates opened on a vast space many football fields long, encompassing within its walls, surprisingly, Tony observed, several churches, colorful Russian Orthodox structures, topped with the ever present onion domes. If any of life's experiences had passed Tony by, it was history, The Kremlin, after all, is where they whacked dissidents, not saved souls, wasn't it? Tony listened to tour guide certify the significance of the churches, until four figures, posed seated around a table, caught his eye: Lenin, Trotsky, Putin and Czar Nicholas. Tony made a move toward the quartet. Janice grabbed at his hand with a look as cold as a Moscow winter, but Tony slipped loose and steered straight for the giants of Russia 's past. and present. “Now this is interesting,” he called back. Tony approached as a potato-fed lady snapped a picture of her husband, mugging between the street actors. The impersonation business was less than sunny; so were the smiles as a few rubles of appreciation exchanged hands. Behind Tony, a breathless Janice, sexy in tight-fitting beige slacks, her wide-brimmed sun hat askew, pulled up abruptly. Tony said, “Get out your digital. Take my picture with them.” Unhappy, Janice complied. Tony folded ten rubles each into the outstretched hands of the four look-alikes. “ Spasiba ,” he said. Their faces lit up. Here was an American who knew how to say ‘thank you' in Russian. As great leaders, you are never too high and mighty to learn, their smiling faces said. * * * Late in the day, Tony and Janice shuffled, along with a new batch of passengers, aboard the river boat, the M/S Serov, named after Valantin Serov, an early 20th Century Russian artist. Quartered in their cabin on the second deck, Tony explored storage spaces, cleverly contrived to exact maximum utility while Janice morphed into an unofficial tour guide. Relaxed on a bunk bed, she read aloud from a stack of tourist brochures. What it added up to in his mind went about like this: Peter the Great, followed by Uncle Joe Stalin, neither candidates for sainthood, dreamed of a waterway linking grim Moscow and flamboyant, Europe-loving St. Petersburg . Over many dead bodies, the waterway inched to completion over the decades. A canal exiting Moscow affords passage of boats, as they sail north, passing the town of Uglich , circling south again, by choice, to Yaroslavl on the Volga , retracing their wakes on the way north again and navigating the vast Rybinsk reservoir. A host of towns and villages dot the landscape on either side of the waterway as it wends a tortuous path to St. Petersburg , or Leningrad , its name, until the crumbling Soviet Union 's dreams of communism faded. At dinner the first night, they chatted with fellow table mates, reliving their lives in the States, and when and how often they had traveled abroad. Diners at other tables around the room chattered much the same, pausing to spoon up borsht, dig into Chinese cabbage with red currants, carrots, and raisins. Barely passable wine, unlike tears of the old song, flowed sparingly. Attractive scenery scrolled by the large dining-room windows as the Serov's bow plowed forward through the canal headed for its ultimate destination, St. Petersburg . The assemblage of passengers, easily detected by obediently displayed name tags, consisted of an international stew of nationalities, mostly Westerners, but a sizable representation from eastern Europe. “I'm always impressed by how well these foreigners speak English,” opined Tiffany Morgan, one of their table mates.” Husband Al smiled wanly. “And isn't too bad, “ Janice said, “that we in the West rarely learn another language.” Out the porthole, Tony thought, goes a fleeting chance for a shipboard friendship. But the dig passed through Tiffany like diuretic tea and she let us know again that her goal of the voyage was to view Catherine the Great's sprawling splendor of her palace in St. Petersburg . “But you must spend some time in the Hermitage, home of Russia 's national treasures,” Janice insisted, never one to let dust settle. Before an evening reception to “Meet the Captain and Crew,” Tony, frowned over the map of the river voyage before reminding Janice that the next afternoon would land them in Uglich. “Oh, yes,” Janice said, her blue eyes sparkling, “that's a special walking tour. We'll see that famous 18th Century Church of St. , Dimitry of the Blood. That's one with blue, spangly domes instead of the gold ones.” A couple of hours later at the Reception, passengers slipped into chairs provided in the main lounge. Low murmurs of conversation, signaling respect for the moment, preceded entry of the Captain, stepping from the 19th Century with full beard and uniform regalia only a true salt of the sea wears with authority. Polite applause. Translation ensued as Helmut, the company tour guide, tucked the event under his protective wing. “ Rad tebya videt ,” said the Captain and six crew members in unison. “And we all know,” prompted Helmut, “they mean ‘nice to see you'.” A few sentences in Russian followed from the Captain, concluded by dasvidania . “He says,” said Helmut, “Welcome aboard. He promises you a safe and enjoyable journey. And goodbye.” Niceties over, the bar opened. “A man of few words,” Tony told Janice over vodka martinis. “I like him. “Strong, silent type. Straight out of central casting. I feel safer already.” Sergey, the amiable bartender, dished a tidbit of inside talk. “Maybe you wonder why Captain is named Ernst Heisinger when he pilots Russian boat. No?” “Well, yes,” said Tony. “Is because he is really German, from East Germany . Ran into trouble there resisting communist collaborators. After Wall crumbles, he came to Russia , learn our language. Now good Captain. See how democracy we are.” Janice waved the loquacious bartender away, as Tony held up a two-finger reorder. “We have to be up early, remember. The walking tour of Uglich.” “I figured we'd run into an u-glich this evening.” * * * Day Six's tour entourage trooped in step behind the local guide whose enthusiasm for the city matched his pride. Not all murders in Russia become tourist attractions, Tony sensed from the start. When a doer of dastardly deeds is a Charles Manson, a Jack the Ripper, or, in the case before them, Ivan the Terrible, horror turns easily into a spectacle fit for public discourse. Our guide was more than eager to describe how Ivan's son was murdered in the Church of St. Dmitry on the Blood. The shoe-leather tour of Uglich opened visitors' eyes to the splendor of Russia's past, colored, unhappily, with the plight of many impoverished citizens, competing with each other to sell souvenirs, brightly, and often elegantly painted eggs a la Faberge and bristling population of nesting dolls, really Matryoshkas. Along the way, Tony nudged Janice gently and gestured side ways with his head. “Notice everywhere we go two photographers from the ship snap the group with 35 mms from every angle. All my nightmare Soviet anxieties are real.” Janice frowned, pursing her full, scarlet-tinged lips. “The Soviets are gone, pffft. Remember how the Iron Curtain lifted, and the Wall came tumbling down?” She was right, of course. Adventures in neo-capitalism were abloom in the land, mostly in the greedy hands of newly-minted billionaire oil barons, casting long shadows over reinvigorated workers, low totem-pole dwellers, who, at one souvenir outlet, sold watches. Not unusual, except the makers of time pieces counted on the sale of each as the day's wages. * * * On a trip from topside to Deck Two, Tony's eye caught a glimpse of Reception's bulletin board, peppered with colored photographs. Curiosity plus a closer look unmasked the mission of the busy-bee photographers, who'd dogged the passengers' trek through town. Nearly every face aboard looked out from color snaps affixed to the cork board. And Janice and Tony gawking at a forest of Blue Onion Domes , pointed out by the local guide. Look. There was Tiffany and hubby Al, their almost new pals from the first day's dinner. Another photo intrigued Tony, the picture of a grim, little man, the lone smoker on the tour, garbed in a suit and tie and toting an umbrella. A passenger behind Tony chuckled. “I see you looking at the umbrella man. East German, I overheard. I wonder if they all still dress like that.” With this night's dinner only an hour away, dawn broke for Tony. The photos, for sale at a bargain few rubles priced below each, exceeded by multi-pixels the fuzzy efforts of most tour members. By breakfast, Tony and Janice noticed, most had been snapped up, including one that had intrigued Tony, the shot of a grim little man, the lone smoker. Funny, Tony thought, how someone so out of date fancied his image not only worth preserving, but also worth buying. Strange world. * * * Like all paid tours, river boat expeditions nurtured the tradition: bored guests are prone to attacks of gloom, best avoided, even at the cost of enlisting an overworked staff as evening diversion. Up front, tour guide Helmut, natty in a pool-table green jacket, preened briefly before announcing the imminent presence of the evening's musicians, who, sang, danced, fiddled and squeezed the accordion with full-throated verve. Tony, nodding approval, turned to Janice, who returned the nod. And it was clear that life--rather, making a living-in the new Russia-- meant doubling in brass. Another surprise. The busy photographers, who earlier shadowed the walking tour, served as the evening musicians, top-quality sound from Moscow 's best schools, too. Morning found the riverboat bound for its next stop, a leg of the trip, requiring the vessel to loop south, eventually docking at Yaroslavl , named for founder, Yaroslav the Wise, a city evoking surviving beauty of Russia 's past. “You know, it's called ‘Florence of Russia,'” Janice, excited by the prospect of relaxing time ashore. And, thought Tony, another day investigating more churches, at least those that had survived Stalin's religious purges. The Serov docked on time, setting off a flurry among passengers, poised to disembark and enter the city. Time dragged on with no official loud speaker instructions. An officer from the crew, looking grim, hurried by, ignoring clusters of passengers puzzled by the unexpected delay. “Something's up,” Tony told Janice, clutching her city tour map. “None of your usual glass-is-half-empty talk,” she said. But Tony was right. Something was up. An air of anxiety slowly enveloped the boat like river fog. At length, the loud speaker crackled, foretelling a message. Tony recognized the voice of tour-leader Helmut Heisinger. “Attention please. There is some unsettling news, the Oxford voice announced. “An accident, it would appear. The Captain. The first mate had to dock the boat. We've phoned the city for medical assistance. I am sorry to report the Yaroslav outing will be indefinitely delayed.” Groans rippled through passengers, huddled in groups, trying to decode the meaning of the announcement. Whatever it was, Tony sensed watching the dock, unease riffled the calm of the July day. * * * Moments later several black sedans, pulled up close to the gangway. A small platoon of men and women, dressed mostly in black, spilled out of the vehicles. The suits, wired at the ear, conferred dockside. A medical van drove up and stopped. Two white-coated attendants stepped out, as the lead suit strode toward them, exchanged words, and returned to his own group. “Cops of some kind,” Tony said. “Do you really think so?” Janice asked with alarm. On board, crew members parted passengers to let four suits make their way to boat's bridge. On the dock, two other official-looking arrivals, sealed the gangway entrance and assumed a wary-guard stance. Just our luck, Tony thought, as he spotted Tiffany and Al bearing down on them. In a Tiffany dudgeon, she exclaimed, “See, just like the old Russia . I knew something like this would happen.” Al tried to console her, a futile gesture. Tony, marshaling a tone of wisdom--one maybe Yaroslav the Wise would approve--suggested a wait-and-see approach. An hour passed, and lack of news or instruction plucked at the tour groups frayed nerves. Then it came with jolting suddenness. The Captain was dead. Gasps and cries of disbelief pulsed through the passengers. “How?” somebody shouted. “What happened?” another demanded. Another voice, not Helmut's, but a Russian, speaking English, measured out his words carefully. “I represent the Yaroslav Police Department. We profoundly regret having to delay your holiday, but a preliminary investigation shows that we deal with a ‘death of suspicious nature.'” Tony whispered, “Translation, murder.” “Shussh,” Janice scolded. “Let's listen.” “We further regret,” the voice continued, “that your boat must remained docked and passengers are forbidden to disembark while further investigation proceeds. I am informed that ample supplies of food and water are aboard. So there is no cause for worry. We will keep you informed as matters proceed.” Tony spoke: “Well, I've checked the 14-day tour guide brochure. Lots of churches, museums and onion domes on the schedule. No murder on the sightseeing list.” Tiffany was not amused. Janice said, “Really, a bit over the top--even for you, Tony.” The Captain's demise cast a pall, but not one dark enough to discourage dinner, which was served by a rattled staff in an atmosphere of buzzing speculation. “Of course,” Tony said, “they suspect the killer's among us.” “But why the Captain?” Janice said. “Seemed such a nice guy.” Finishing up the last of the dessert, Serdechko, Tony pushed away from the table, reminding everyone that, despite the day's tragic events, the bar was open. Why Sergey, the bartender singled Tony out as a confidante, wasn't clear. Tony did have a bad habit of over tipping, so maybe that explained Sergey's whispered report. He had learned from the gossip mill, a device that regularly grinds for bartenders from London to Singapore , that poison is what killed the Captain. An easy guess, Tony thought, since poisoning of ranking Russian citizens was epidemic these days. “We'll see if they slap the Chef in the brig.” Not that simple Sergey went on. A different type of poison, not the famous radiation dose, everybody knows about. What the two medics found was a little red mark, barely detectable in the Captain's thigh. The Detective who spoke to everybody on the loudspeaker thinks the poison entered at that spot. Tests in a Yaroslav lab proved it to be Ricin, an old, but reliable toxin. Who did it and why are the big questions? The police know someone, someone who must have known the Captain, a nonsmoker, was in the cabin with him. A cigarette butt in an ash tray suggested that. * * * Next morning, the main police investigator, previously just an anonymous voice, identified himself as Detective Viktor Markov. The loudspeaker voice we'd heard matched his strong, resolute countenance, as he mingled with knots of passengers and asking whether anyone had seen anything--anything--unusual that might be relevant to the Captain's death. He handled an avalanche of trivia and speculation with good humor. At one point, he clarified his request. “A person or persons, among you, perhaps furtive, uncomfortably out of place.” he coached. At the request, Tony perked up. Janet warned, “Don't get involved.” “But it's murder. Look, I think I know what the Detective means. You can jog my memory.” “I can?” “Remember, the picture bulletin board, where we first saw that guy in the suit and tie, carrying an umbrella? Well, on our walking tour, he was always in uniform. Always carried an umbrella, even when the forecast was for sun.” “Well, he was pretty nondescript. Not American. And another thing. He never wore his tourist name tag. Smoked a lot. ” “Exactly. Tried to duck the picture takings. Didn't want his presence known.” “But you can't single him out for looking odd.” “We're just the messengers. We'll let Markov judge the importance.” Detective Markov sat with Tony and Janice in an empty cabin. “The man you describe and the pictures. Where are they?” Tony thought a moment. Janet chimed in, “They're gone from the wall, of course. “But the ships photographers should have copies.” “Could you point this man out?” Markov asked. “Actually, we haven't seen him lately.” “He could be hiding, lurking out of sight at the very least If I get that picture, I can match it with his passport in the boat's safe. Then we can track him down.” * * * Flushing out the umbrella man proved easy, once Markov had his picture. Ernst Schur by name. Markov explained his special obligation to explain things as thanks for the help from Tony and Janice. “An old Stasi trick,” Markov said. “The notorious East German secret police.” “The Ministerium for Staatssicherheit, organized to create fear to halt any East German unrest. Before the wall crumbled, Stasi counted on informants, thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands of informants to cower dissidents. Ernst Schur was on of the rats, a small one at that, serving to this day as a flunky volunteer in the Stasi Museum in Lichtenberg.” “But why the Captain?” “He worked the underground, resisting East Germany 's corruption.” Tony glanced at Janice. “Remember, that's what Sergey told us at the bar. The Captain got out of the East German mess and came here, an honest, hardworking man.” “Before that he faced off with Ernst Schur, actually roughed him up, pointed him out as a collaborator,” Markov said. “Schur never forgot, never forgave. An unimaginative, little toady. Even stole the murder idea from the 1970's, when a hit man killed a Bulgarian author for anti-regime writings. “The umbrella, developed by the KBG, shoots a pinsize pellet laced with Ricin. Victim feels only a sting, but soon he's dead. Lifted from the Stasi museum, along with a tie-pin camera. That's the reason for the coat and tie costume.” “The weapon, okay. But what about placing him at the scene of the crime?” “His smoking you two noticed. The cigarette butt left in the Captain's cabin. We're running the DNA tests. We'll wait, but we've got no doubt. Meanwhile, possession of the weapon, the umbrella, hidden in Schur's cabin is enough to hold him.” etective Markov paused and smiled. “Please accept our nation's gratitude for your help. And bon voyage.” |

|

|

Past issues and stories

pre 2005.

Subscribe to our mailing

list for announcements.

Submit your work.

Advertise with us.

Contact us.

Forums, blogs, fan clubs,

and more.

About Mysterical-E.

Listen online or download

to go.

|

|

|

|

|